Administration of the project

Medical textiles and tribology

NOT LONG BEFORE MY LAST SKI TRIP, I was having a lot of lower back problems stemming from a bad fall years ago. Without getting into too much blood and gore, I have a pinched nerve and the associated arthritis from long-term inflammation. So the fix, at least enough to get through the ski trip, was a steroidal anti-inflammatory injection in the spine for the pinched nerve and a patch that was stuck on the lower back which slowly dispensed an anti-inflammatory for the arthritis. Well, the fix worked well enough, and I had a good week of skiing. But the experi-ence got me thinking about the patch. Like most things in the sciences, it seems simple enough on the surface, but as we peel back the layers of the onion, we find there is much more to it.

So I ran across an article titled Tribology and Medical Tex-tiles: A Brief Outlook, by Harshvardhan Singh, an automotive engineer who has worked as a scientist (tribotesting and lubricant analysis) at Austrian Center of Competence for Tribology, Wiener Neustadt, Austria. Well, I was astounded to see that rather than being written by a bunch of doctors, this comes from one of us! A tribologist, no less! So let’s see what I learned. In the world of medicine and pharmacology, drugs can be taken by the patient in many forms such as by inhalation, injection, dissolving the drug under the tongue or via patch on the skin, as in my case. This patch—in medical terms—generally comes under the category of a medical textile.

Medical textile is a general term that describes a textile structure, which has been designed and produced for use in any of a variety of medical applications, including implantable applications. I had never heard this term, and use of medical textiles involves two key aspects: drug loading and drug release. In other words, how much and how fast you get the drug. Drugs can be loaded onto textile fibers and fabrics via a number of methods such as by using ion exchange, hollow fibers and surface coating. Drugs can be released in a controlled and prolonged fashion, keeping in mind drug concentration and matrix architecture.

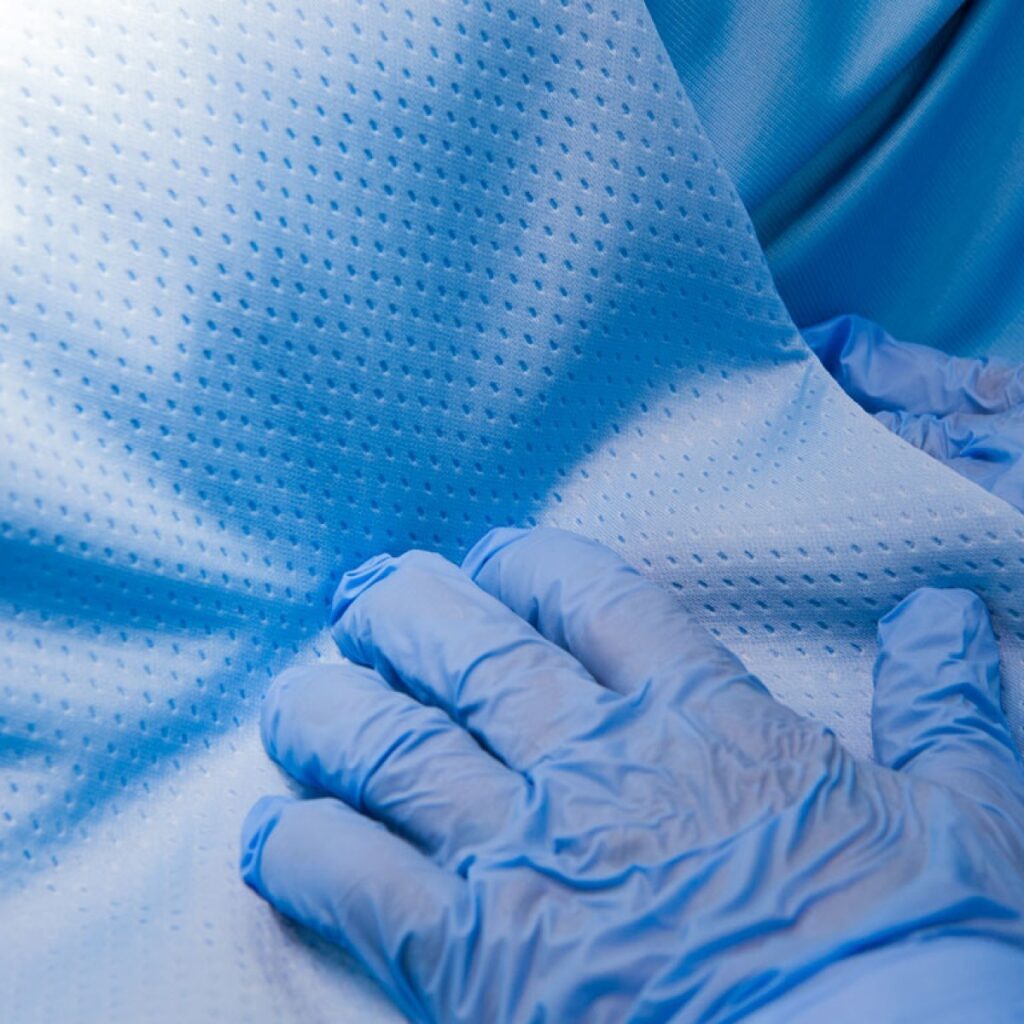

Medical textiles are not just limited to drug delivery bandages like I had. They also include hospital bedsheets, surgeon’s wear, wound dressings, diapers and sanitary towels. Who would have guessed medical bedsheets, let alone some of the other items? These also are available in a wide variety of forms: braids, wovens, knits, non-wovens and hybrids. Since such items are used in the medical field, the quality of these medical textiles has to be of very high standards.

Some of the key qualities include:

- Biocompatible

- Good resistance to bacteria

- Free from impurities

- Dust repelling ability or low-dust absorption rate

- Good permeability for air

Decubitus ulcers are found primarily in patients left in bed or in a wheelchair for long periods of time. Coma state, heart surgeries and some pregnancies normally require complete bed rests. Prolonged pressure, friction and shear forces, as well as moisture at the skin-textile interface, are some of the causes of decubitus ulcers. Well, this is all well and good, but what really got to me was the tribology of medical textiles.

So the combination of friction, pressure and moisture can strongly decrease blood perfusion and can cause harm to skin texture. Well, these are the kinds of things tribologists understand. In fact, several tribologists are trying to develop new fabrics or optimize current fabrics used in hospital bedsheets by conducting tribological tests over various fabrics in dry and wet conditions. Their main emphasis is on reducing friction and shear forces acting on the skin of relatively immobile patients. Efforts also are being made to make the skin textile interface drier since it has been observed that the friction between skin and textiles increases with interfacial moisture.

Researchers also are working on making more skin-friendly materials. In one of the studies, tribologists conducted 3D topography of a normal hospital bedsheet and a new bedsheet with a regular surface structure. It was found that the latter offered a smaller microscopic contact area (up to a factor of two) and by a larger free inter-facial volume (more than a factor of two) in addition to a 1.5 times lower shear strength when in contact with counter surfaces. Through the same study, penetration of the textile surface asperities into skin and the ratio of real and apparent area of contact between textiles and skin also was found. These are all concepts that are familiar to tribologists.

Further, scientists are exploring the extraordinary properties of graphene and carbon nanotubes to motivate the development of methods for their use in producing continuous, strong, tough fibers that can retain their microshape. Previous work has shown that the toughness of the carbon nanotube-reinforced polymer fibers exceeds that of previously known materials. Can the use of graphene also moderate friction through a strong fiber that holds its shape while also lowering friction? I don’t know, but it sounds good.

Nonetheless, we can begin to see how tribology can be applied in the medical textile industry in order to provide high levels of comfort to the patients and disease treatment/ prevention. In my case, it was hard to tell if the patch really helped since by the end of the day of skiing, the patch had slipped or even kind of balled up. This was because skiing is pretty physical, and the patch was located where my waist-band was rubbing on it. Since my patch also was a free sample my doctor gave me, I’m guessing it was on the low end of what is possible. For certain, tougher materials, less friction and maybe a better adhesive mechanism could have helped.

Once again, you just never know where one of us just might show up working behind the scenes to enable some new science or technology.

Dr. Robert M. Gresham

STLE’s director of professional development.

Be the first to comment